We really ask too much of our internal combustion engines--compression needs a cool environment and combustion a hot one--and the compromises made to accommodate those demands lead to abysmal efficiency. So a San Diego-based company is turning that around by splitting the engine into two parts--a hot half and a cold half--to potentially boost efficiency by 50 percent.

A conventional four-stroke engine has four essential motions: the intake stroke where the piston draws in fuel (downstroke), the compression stroke where it packs the fuel (upstroke), the combustion or power stroke where the fuel ignites (downstroke), and the exhaust stroke (upstroke) that clears the leftovers from the cylinder and prepares for a new intake stroke.

The first two strokes work optimally in a cold environment, while the last two work better when the cylinder is hot. To compromise, the radiator is constantly channeling heat away from the cylinders, energy that is lost forever. Moreover, compression happens optimally in a small cylinder, combustion in a larger one with more space for the fuel-air mixture to expand fully (more energy is lost to heat as exhaust here). Again, the average piston size is a compromise between the two.

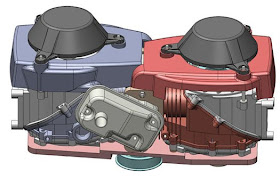

Tour Engine in San Diego is tired of compromising. Its Tour engine breaks down the strokes into two different but connected cylinders: a smaller cold cylinder for the intake and compression strokes feeds the compressed fuel into a larger hot cylinder for ignition and exhaust.

Where conventional engines would waste 40 percent of their energy to cooling and 30 percent more to exhaust (that’s right, your car is only converting about 30 percent of its fuel to actual work), the Tour engine, in theory, could immediately boost engine efficiency by 20 percent. Ultimately, engineers there think their tech could boost efficiency by more like 50 percent.

Splitting cylinder functions isn’t a completely novel idea, but the idea of separate hot and cold cylinders that optimize each stroke is pretty intriguing.

by "environment clean generations"

With fire, the maximum temperatures are reached when an equilibrium is established as the increase of cold fuel and air begins to cool the fire rather than heating it.

ReplyDeleteTo melt (pure not cast) iron or steel, exhaust heat is stored in the walls of the exhaust ports and after a time the direction of flow of air and fuel is reversed with Fuel-Air being pre-heated in the former exhaust.

Monte Haun mchaun@hotmail.com